The novel Manon Lescaut was first published in 1731. The events described by Abbe Prevost took place in the first half of the 18th century. “They happened, at that very period, to be sending out a number of convicts to the Mississippi”, the author notes. Among them, Manon Lescaut was to be shipped to a penal colony in Louisiana. The Chavalier des Grieux follows her and bitterly laments her fate: “If anything caused me uneasiness, it was the fear of seeing Manon exposed to want. I fancied myself already with her in a barbarous country, inhabited by savages.” He then quickly corrects himself making an interesting remark about the savages: “I am quite certain (…) They will, at least, allow us to live in peace. If the accounts we read of savages be true, they obey the laws of nature: they neither know the mean rapacity of avarice, nor the false and fantastic notions of dignity, which have raised me up an enemy in my own father. They will not harass and persecute two lovers, when they see us adopt their own simple habits.”

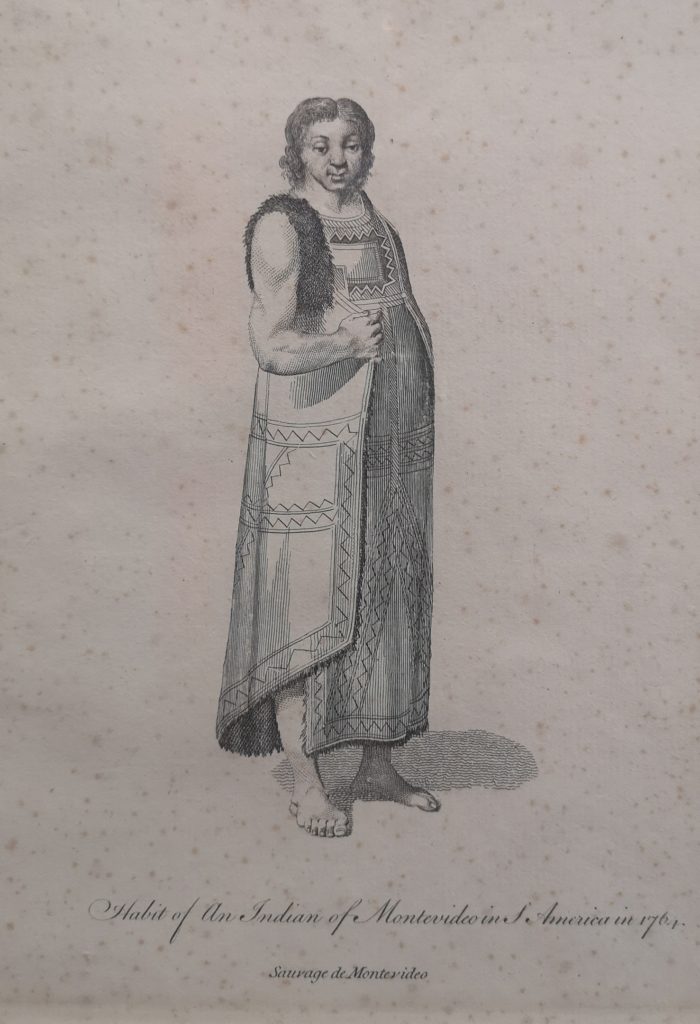

One of the engravings we observed at the history museum of the capital of Uruguay (Museo Histórico Cabildo de Montevideo) is titled “Savage of Montevideo” (“Sauvage de Montevideo”). Just above this inscription, there is another one, “Habitat of An Indian of Montevideo in S. America in 1764”. It is difficult to say what was savage about the appearance of that man, as documented by Dom Pernety, whose name appears on a plate alongside the engraving. But none other than The Savages (Les Sauvages) is what Pernety calls all of the natives of North and South America.

Unlike Abbe Prevost, who only collected existing travel materials and published them in his encyclopedia, Dom Pernety was a member of the previously mentioned Bougainville’s scientific expedition to the Falkland Islands in the South Pacific, which took place from 1763 to 1764*. Pernety wrote a book about his journey titled The History of a Voyage to the Malouine (or Falkland) Islands.

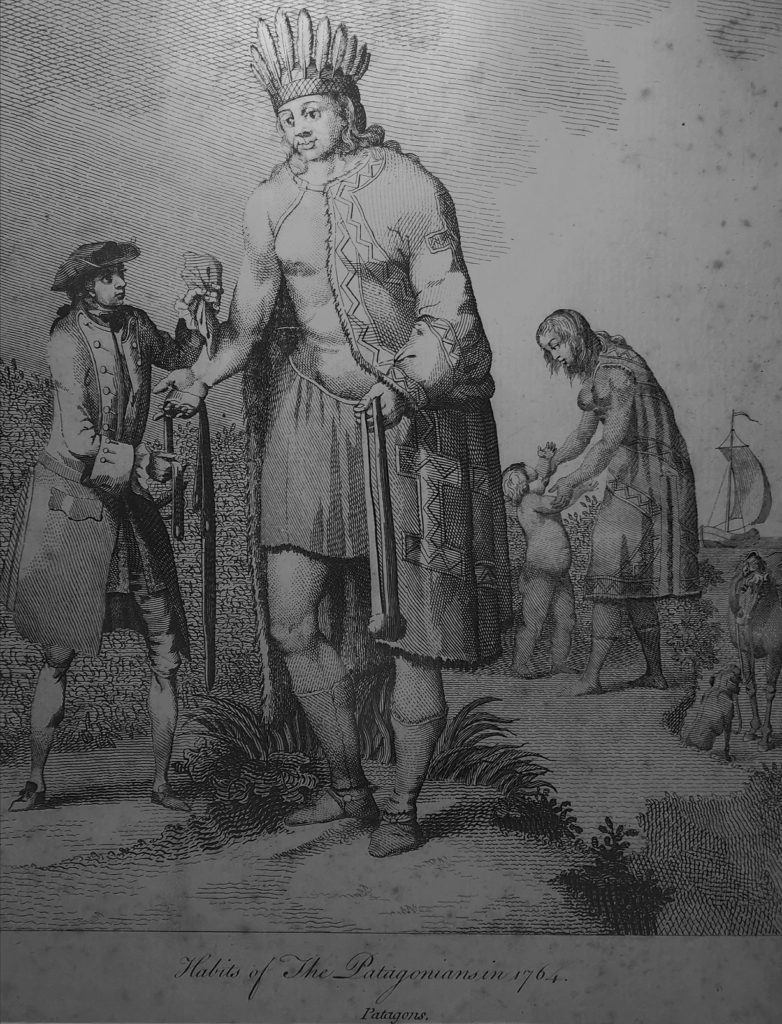

In this book, in addition to the “Savage of Montevideo”, there is another very interesting engraving that we were able to see at the National Historical Museum of Buenos Aires (Argentina). Also dated 1764, it is titled “Habits of the Patagoniansin – Patagon”.

The following information is found just beside the engraving:

“This reproduction from the 18th century shows an original inhabitant of Patagonia represented as a giant. From the 16th to the 18th century, travelers and seafarers of different nations report seeing men of a gigantic height on one of the parts of Strait of Magellan coasts. The myth of the Patagonian giants is part of the European imagination and perception of the American continent.”

Although the National Historical Museum of Buenos Aires attributes the gigantic height of the Patagonians to the imagination of the Europeans, we were able to find different information in Dom Pernety’s book. Describing his numerous encounters with the inhabitants of Patagonia, he notes the following:

“The presents we made them consisted in some pounds of that red which we call vermilion: and some red woolen caps, which however not one of them could put his head into: these caps though very large for heads of a common size, were still too small for them (…) Here they examined the Patagonians at their leisure, and found them to be men of the highest stature: the least of them was five feet seven inches (French measure = 185cm), and of a bulk beyond the proportion of their height, which made them appear less tall than they are.”

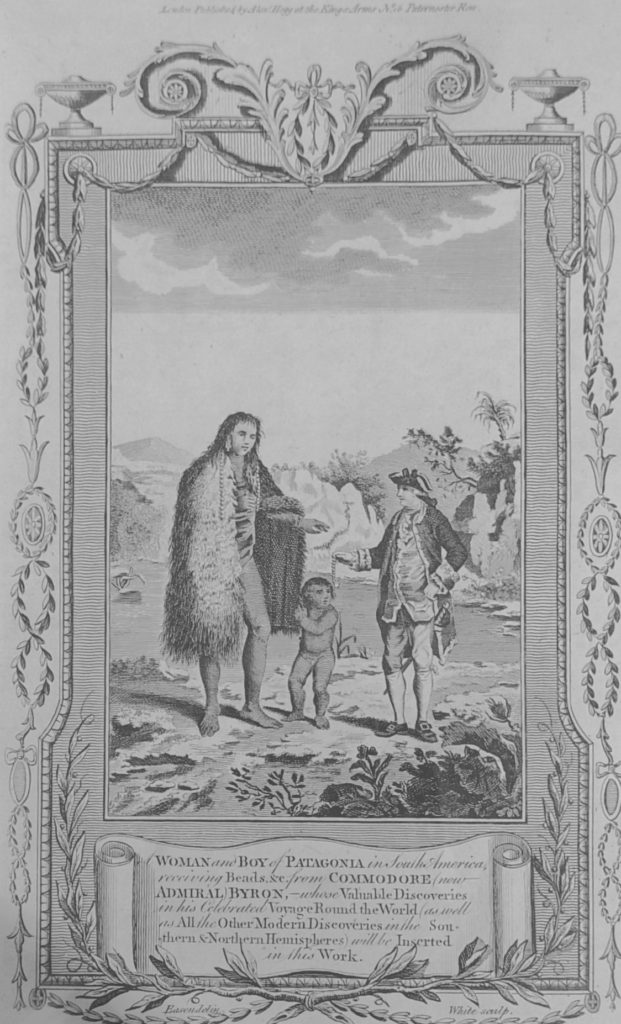

An engraving depicting a female resident of Patagonia of incredibly tall stature maybe be found at the Historical Museum of the National University of Cordoba (Argentina). The following explanation is presented in the lower part of the engraving dated 1784:

“Woman and boy of Patagonia in South America, receiving beads from Commodore (now Admiral) Byron, – whose valuable discoveries in his celebrated voyage round the world (as well as all the other modern discoveries the Southern and Northern Hemispheres) will be inserted in this work.”

This refers to one of the publications about John Byron’s circumnavigation of the globe***, which contains a description of people of gigantic stature, including women:

“The women, whose large and masculine features corresponded with the enormous size of their bodies (…) Their middle stature seemed to be about eight feet (French measure = 2m 60cm), their extreme nine and upwards (French measure = 2m 90cm), though we did not measure them by any standard and had reason to believe them rather mere than less (…) The method he (Byron) made use of to facilitate the distribution of them (strings of beads), was by making the Indians sit down on the ground, that he might put the strings of beads round their necks; and such was their extraordinary size, – that in this situation they were almost as high as the Commodore when standing.”

It is interesting to note that if Dom Pernety only called the indigenous peoples savages, neither John Byron nor Louis Antoine Bougainville ever used such words in relation to the natives.

Philibert Commerson, a well-known French naturalist, another participant in the circumnavigation of the globe of 1766-1769 led by Bougainville, spoke especially enthusiastically of the indigenous peoples. He was particularly fond of the inhabitants of the island of Tahiti:

“Born under the most beautiful sky, nourished by the fruit of an immensely rich land that is fertile, despite being uncultivated, governed by fathers of families rather than by kings, they know no other God than Love”.****

______________________

*The expedition to the Falkland Islands was undertaken two years before the famous circumnavigation of the globe of 1766-1769

**Journal historique d’un voyage fait aux îles Malouines en 1763 et 1764 pour les reconnaître et y former un établissement et de deux voyages au détroit de Magellan avec une relation sur les Patagons (2 volumes, 1769)

***John Byron (1723-1789), British admiral, grandfather of the famous poet George Byron. Between 1764 and 1766, Byron completed a successful circumnavigation of the globe as captain of Dolphin, described in the book A voyage round the world in his Majesty’s ship The Dolphin, commanded by the Honorable Commodore Byron…written by an Officer on Board the said Ship

****Le journal de Philibert Commerson (extrait du texte publié dans le Mercure de France, novembre 1769)